The above image includes a framed rendering using Larson Juhl's Arqadia 90971.

Simply scroll through the page or click one of the links below to learn about this artwork.

• UNCLE SAM AND DR. SEUSS

• FROM WWII TO CHILDREN'S BOOKS

• DR. SEUSS'S POLITICAL CARTOONS

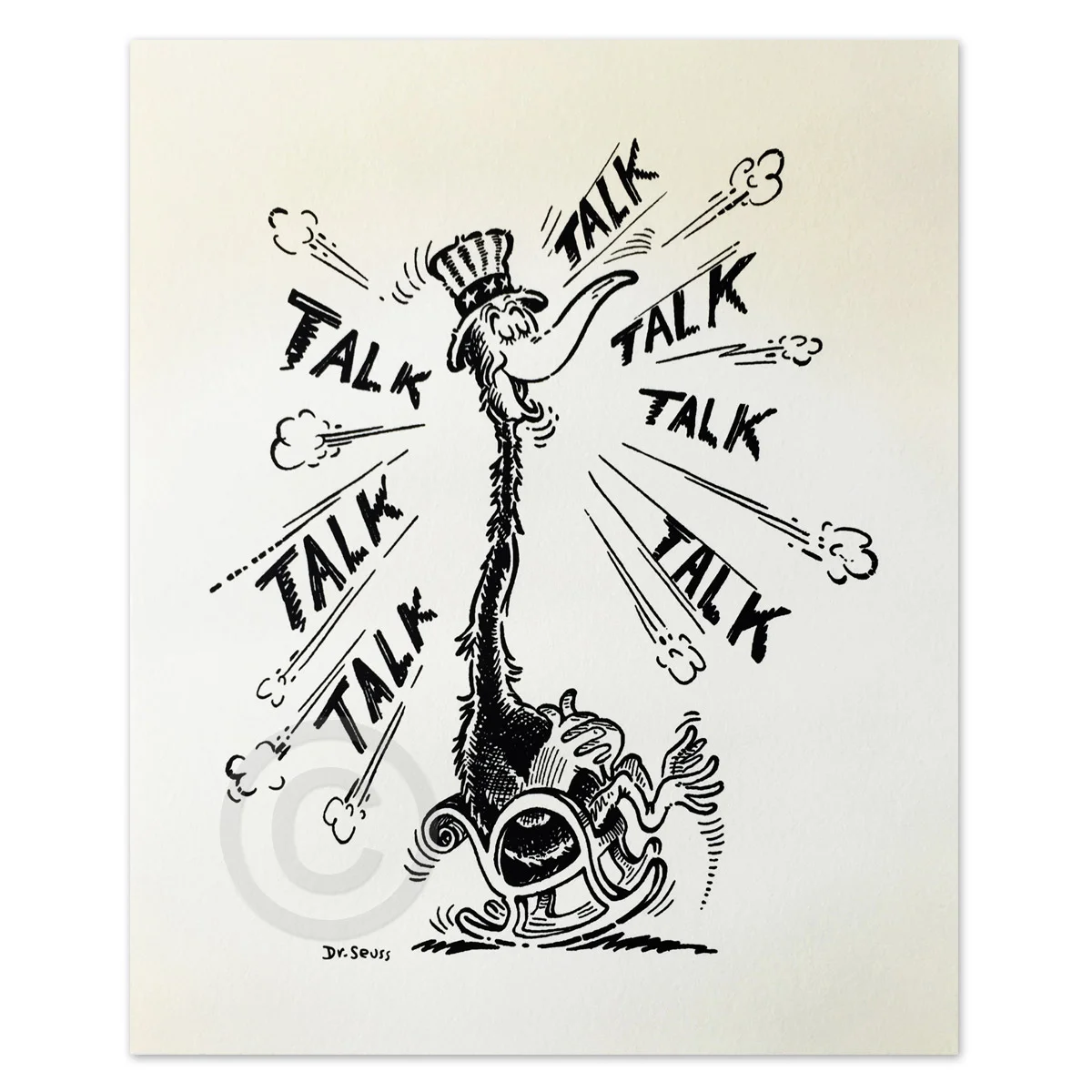

Talk Talk Talk

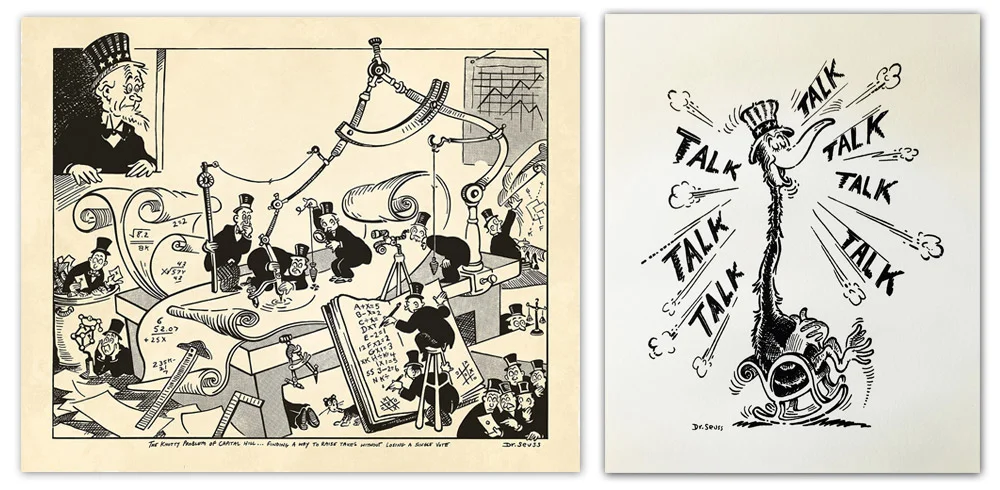

Dr. Seuss’s 1941 artwork, Talk Talk Talk, presents one of the quintessential examples of his enduring relevancy. Throughout the career of Theodor Seuss Geisel (aka Dr. Seuss), Ted grasped a seemingly prophetic quality that makes his themes as pertinent today as when they were first created. Originally featured on the cover of PM’s May 8, 1941 edition, this powerful World War II editorial cartoon instinctively sums up the current mood of our country during this highly charged 2016 election season. The enduring chasm between political “talk” and “action” is the persevering component that makes this artwork as significant today as it was 75 years ago.

“Ted grasped a seemingly prophetic quality that makes his themes as pertinent today as when they were first created.”

Towards the end of his life, Ted’s biographers asked if something remained unsaid. A few days later he handed over a piece of paper with these words: “The best slogan I can think of to leave with the U.S.A. would be: ‘We can . . . and we’ve got to . . . do better than this.’”

Many have delighted in the idea of what Dr. Seuss might deliver if he were to apply his sociopolitical humor to today’s politics. Look no further than Talk Talk Talk, an artwork Dr. Seuss could seemingly have created specifically for this modern-day presidential campaign.

Serigraph on Acid-Free Paper, 18.75" x 15.25"

Limited Edition of 850 Arabic Numbers, 99 Patrons' Collection, 155 Collaborators' Proofs and 5 Hors d'Commerce.

Uncle Sam and Dr. Seuss

This historic recruiting poster was used during both World Wars. In Talk Talk Talk, Ted’s sneetch-like character wears a version of Uncle Sam’s familiar and patriotic top hat. But here, with a wry Seussian twist, Ted diffuses the credibility of this propaganda icon and instead creates a work highlighting the chasm between “talk” and “action” in our nation’s government.

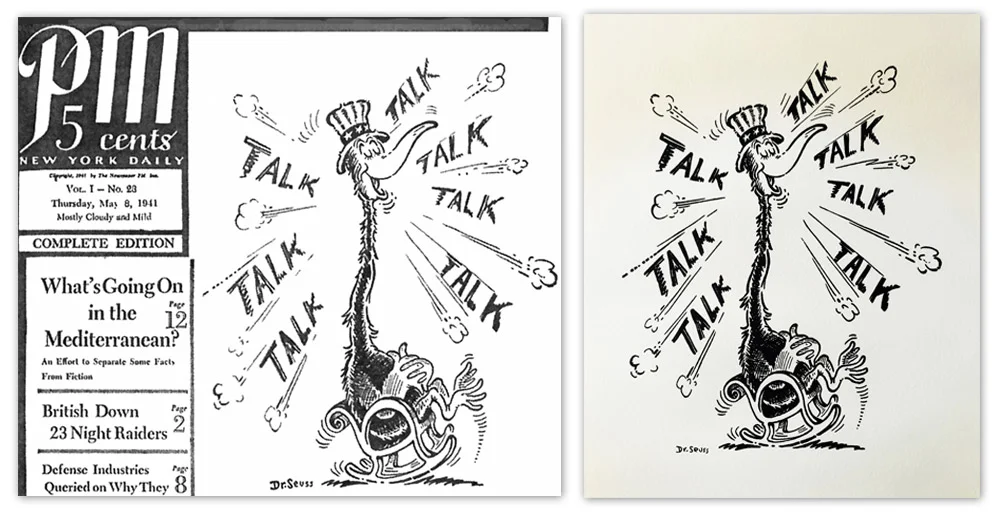

Left: Original context in PM, May 1941 Right: Final Serigraph on Paper, 2016

From World War II to Children’s Books

Ted created more than 400 political cartoons for PM, the first one published at the end of January 1941, the last one on January 5, 1943, two days before Ted volunteered and was inducted into the Army. Early on his publisher requested five completed cartoons every week, a frenetic pace which honed Ted’s skills as a sharp and quick illustrator. This challenge also sharpened his ability to distill complex issues down to simple, powerful messages tucked within the phrases he wrote to accompany these cartoons.

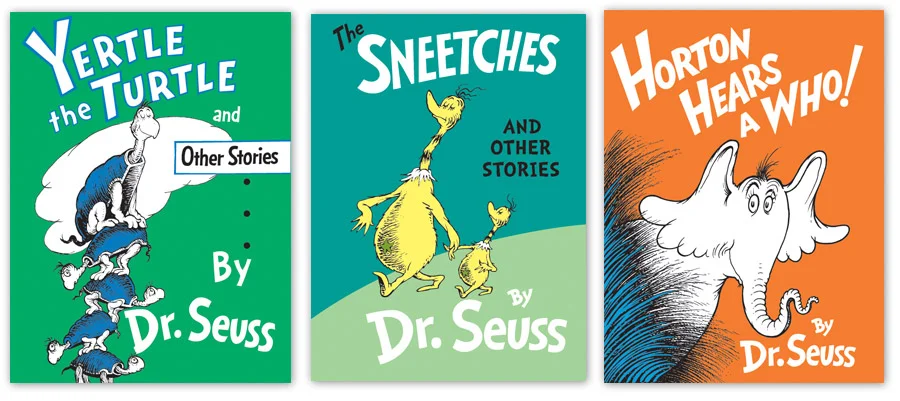

Ted would continue on this path throughout his career, conveying vital life-messages through the pantheon of characters that populated his artwork and books. So deft was he in this technique that few overtly recognized the many sociopolitical statements made over his 70-year career:

Yertle the Turtle was written as an argument against Fascism.

The Sneetches as an argument against discrimination.

The Lorax as an argument for resource conservation and corporate responsibility.

Horton Hears a Who! as a parable on democracy.

The Butter Battle Book as a visionary tale on the nuclear arms race and mutually assured nuclear destruction.

The Cat in the Hat was written as a statement against illiteracy and conformity.

Neil Morgan, co-author of Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel, said this about his friend: “In the end, what drove Ted, I think, was to be useful to the world. He sent those wacky warriors he created out to wage the battles of the underdog, with whom he always felt a kinship—the battles against illiteracy, against environmental ruin, against greed, against conformity, against the arms race. He taught generations of children that it was fine to be different, and it was even better to do good, but that it all should have some fun about it.” [1]

1. Theodor Seuss Geisel, Reminiscences & Tributes (Hanover, New Hampshire: Dartmouth College, 1996), 22.

“He taught generations of children that it was fine to be different, and it was even better to do good...”

Dr. Seuss's Political Cartoons

By the fall of 1940, Ted Geisel had become unnervingly haunted by the war in Europe. Eventually, he showed one of his politically-charged cartoons to a friend who had joined the staff at PM, New York City’s new daily newspaper. When PM’s publisher saw it, he immediately recognized the quick wit and powerful impact of Ted’s work, publishing the cartoon on January 30, 1941, and hiring Ted to create a series of ongoing commentary.

Immediately, Ted was all in. “PM was against people who pushed other people around,” he said. “I liked that.” [2] As for the staff itself, he regarded them as “a bunch of honest but slightly cockeyed crusaders.” [3] Because the paper was understaffed, everyone had to stay focused on their own work. Ted found himself completely unfettered and able to expose whichever Axis power-monger he wished. His two years with PM resulted in more than 400 World War II cartoons.

2. Judith and Neil Morgan, Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel (New York: Da Capo Press, 1996), 101.

3. Morgan, Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel, 103.

The Art of Dr. Seuss Collection political cartoon releases:The Knotty Problem of Capitol Hill...Finding A Way To Raise Taxes Without Losing A Single Vote (left) and Talk Talk Talk (right)