Simply scroll through the page or click one of the links below to learn about this artwork.

INTRODUCTION

THE NAMING OF A LEGEND

EQUALITY

FAITHFULNESS

HUMANITY

Serigraph on Paper, 29" x 32" with deckled edges

Limited Edition of 395 Arabic Numbers, 99 Patrons' Collection, 155 Collaborators' Proofs and 5 Hors d'Commerce.

An additional 60 prints will be specially reserved in commemoration of the 60th anniversary of Horton Hears a Who!

Introduction

Dr. Seuss had a fascination with animals that began when he was two years old and the family moved to the Fairfield Street house that would be Ted’s home until leaving for Dartmouth. From his open bedroom window, Ted could hear the night cries of animals at the Springfield Zoo in nearby Forest Park. It wouldn’t be long before excursions to the Zoo were a regular occurrence for Ted and his sketchpad—that’s when fascination turned to love.

In Horton Hatches the Egg (1940), the compassionate pachyderm named Horton was born. Then in 1954 with the publication of Horton Hears a Who!, this classic creature, with his soulful eyes skyrocketed into one of the most heroic children’s book characters of all time. To this day Horton remains a lasting symbol of equality, faithfulness, and humanity.

The impact of this book, as well as the 2008 emergence of Horton as an international film star, continue to instruct new generations of children with enduring messages as applicable to today’s anti-bullying campaign, as they are to the long revered values of honesty and loyalty.

In celebration of the 60th anniversary of this literary milestone, we announce the release of a very special print edition to commemorate Horton’s cultural impact.

An illustration from a 1938 “animal” short story by Dr. Seuss.

The Naming of a Legend

When Theodor Seuss Geisel first introduced his iconic elephant in the 1940 book, Horton Hatches the Egg, he labored over the name choice. Horton was alternately called Osmer, then Bosco, then Humphrey. Finally Ted chose “Horton” after his Dartmouth classmate, Horton Conrad, linking forever a classy name with these classic words: “I meant what I said, and I said what I meant . . . An elephant’s faithful—one hundred per cent!” Horton Conrad was the advertising manager for Dartmouth's Jack-O-Lantern when Ted was editor-in-chief.

Fourteen years later Horton would find literary immortality in Horton Hears a Who! with his straightforward proclamation: “A person’s a person, no matter how small."

Equality

“I’ll just have to save him. Because, after all,

A person’s a person, no matter how small.”

There can be no doubt that World War II profoundly affected Ted Geisel. He devoted seven years of his artistic life to not only cartooning and commenting on it, spurring Americans to action, but also was one of those “older creatives” who eventually enlisted, wanting to serve in whatever way they could.

On January 7, 1943, Ted was inducted into the Army as a captain attached to Frank Capra’s celebrated wartime documentary filmmaking unit. In connection with this work, he shipped out to Europe in the fall of 1944, returning to civilian life on January 13, 1946. The war and its aftermath didn’t just make a solider out of Ted; it made a crusader of him. Despite his early wartime cartooning characterizations, Ted would come to apply his concept of equality to humankind in general. Seuss historian Dr. Charles Cohen said, “Ted’s long maturation process helped him surmount the attitudes of his day to become a pioneer in the fight for equality, so that children would grow up already knowing what it took him several years to recognize.”

Faithfulness

“I meant what I said

And I said what I meant . . .

An elephant’s faithful

One hundred per cent!”

(Horton Hatches the Egg – 1940)

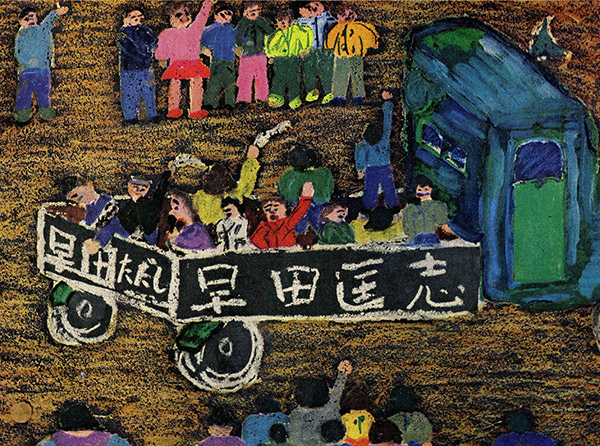

A defining moment for Ted came on March 23, 1953 when he departed for a six-week assignment in Japan—under the auspices of the Ford Foundation—to determine the effects of World War II and the immediate post-war era on Japanese children, ages 11 to 18. The ultimate goal was to learn how the years of American occupation had changed their aspirations. Ted’s Dartmouth buddy, Professor Donald Bartlett, who had close diplomatic ties in Japan, arranged with 100 teachers in Kyoto, Osaka, and Kobe to have their students draw pictures of what they hoped to be when they grew up. Almost fifteen thousand drawings were submitted for Ted to analyze; he brought them home in huge wicker trunks.

This is one of the student drawings that Ted collected. It was made by an 11 year-old boy, who described it as a depiction of a political campaign, "Vote for me. I shall make Japan a good country so there will be no more wars."

In the fall of 1953, as a direct result of his findings, Ted began work on Horton Hears a Who! The theme of the book, “A person’s a person, no matter how small,” grew out of these Japanese school visits, where the importance of the individual was considered an exciting new concept. Ted dedicated the book to his “great friend” Mitsugi Nakamura, dean of Doshisha University in Kyoto, the University founded by Donald Bartlett’s parents. Without Professor Nakamura’s influence, the project wouldn’t have come to fruition and this particular story about Horton would never have been written.

“The theme of the book, “A person’s a person, no matter how small,” grew out of these Japanese school visits, where the importance of the individual was considered an exciting new concept.”

The Horton Hears a Who! manuscript was delivered to Random House in January 1954 and released that August. Ted’s findings, “Japan’s Young Dreams,” were published in the March 29, 1954 issue of LIFE magazine.

The connection between Ted and Professor Nakamura was instant and warm, with both men eventually visiting back and forth, even hosting each other’s friends as the years passed. The San Diego Union reported on December 6, 1963: “Mitsugi Nakamura, dean of Doshisha University in Kyoto, Japan, who has been host in Japan to many from this area, will be introduced to entertaining, Occidental style, by those who have enjoyed his hospitality. He will arrive Sunday to be the house guest of Mr. and Mrs. Theodor Geisel of La Jolla, who will give a dinner party in his honor. Dean Nakamura is the father of Miss Yasko Nakamura, who has completed her education at Claremont College sponsored by Mr. and Mrs. Geisel.”

Humanity

“They’ve proved they are persons, no matter how small.

And their whole world was saved by the Smallest of All!”

Philosophy Now is a British periodical. In 2008, contributor Todd Walters wrote a fascinating piece after just having seen the movie, Horton Hears a Who! In this excerpt he references A.O. Scott’s 2000 New York Times Magazine essay on Dr. Seuss, “Sense and Nonsense.”

“One major downside of autocratic regimes is the dehumanization of the individual; and nothing defines Horton Hears a Who! more than its famous admonishment: ‘A person’s a person, no matter how small.’ A.O. Scott commented on this anti-dehumanizing dynamic in Seuss’s body of work too, when he noted that ‘An overt concern with social justice resounds through the anti-Fascist allegory of Yertle the Turtle, the satire of racism in The Sneetches, and the humanism of Horton Hears a Who!’ It is exactly that humanism—which is the central lesson of the Horton story and this lesson—we shouldn’t have to be reminded, is worth teaching over and over and over again, to both children and adults alike. The message of the worth of individuals and the danger of autocratic power was relevant when the book came out in 1954 . . . and remains relevant today.”

“The message of the worth of individuals and the danger of autocratic power was relevant when the book came out in 1954 . . . and remains relevant today.”